1. A REFLECTION ON THE DE BONO HATS WIKI ACTIVITY

The digital era is upon us and it is very safe to say that our generation is the one walking on the wall that divides the analog and digital eras. The more we walk this wall, the smaller the analog world becomes behind us. Sometimes, we are affected by nostalgia and end up buying an old vinyl or that old camera that looks good in your lounge; it no longer works, but nostalgia prevents us to leave it behind for the moment.

For most us, technology has changed our lives forever. We do banking faster, find information (good and bad) within seconds and make the most of social media, where everyone is an expert at something. Today mobile phones and other devices are everywhere, and not having one or two of them makes you a weirdo. How dare you not be on Facebook?, what’s wrong with you?. This “requirement” to have an online identity and presence puts pressure on our shoulders because now we not only have to deal with the physical world (work, study and do what people do during their lives), but also deal with what this author calls the “online dramas” that the connected life brings us everyday. Ok, we talked about the pressures faced by the grown ups here, but what about the people that grew up in a digital world and that see interconnectivity as the norm?.

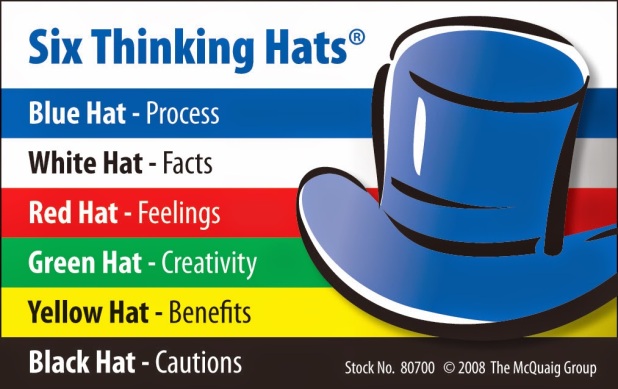

This week’s discussion is somewhat a very provocative and intuitive, task called “De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats”. It is the opinion of this author that one of the many keys to promote thinking is to provoke the subject/student to a new, and sometimes different, perspective or path; this activity has simply done that in a very efficient way. Briefly, the de Bono process broke down our thinking process into six components, which provided the respondents with a variety of approaches within thinking and problem solving. In summary, it seems reasonable to expect that the respondents would see the issue of mobile phones inside a classroom from a variety of angles. This activity could be used for a number of sensitive subjects, and it is vital that people answering the questions are true to their beliefs and open minded enough to respect people’s answers. I couldn’t help but to ask myself after I finished the activity, “what would kids between 12 and 18 years of age answer during this activity?”.

Fig.1. The Six Thinking Hats method developed by Edward de Bono. Source: The Mcquaid Group.

Case study

I realised that issues such as mobile phones inside classrooms will always spark controversy, since people have very personal answers for this issue. That is significant in itself, since my position as an educator requires me to follow and enforce a number of rules, but also to understand how such rules might look weird, useless, and a pain to students. It is the view of the one who writes to you that mobile phones have a place inside a classroom as long as they are used for designed lessons. For example, they should be reserved for times where they provide an opportunity for students to engage in ‘modification’ and ‘transformational’ activities that enhance higher order thinking in the classroom.

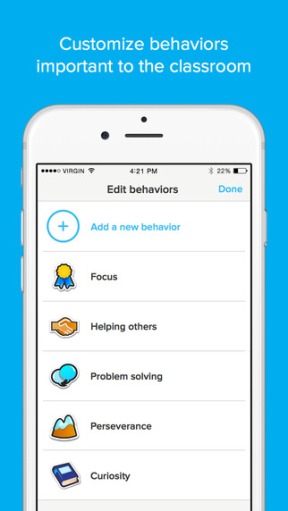

We could use mobile devices, such as tablets and phones, to engage students within a Connectivistic framework (using my right to use artistic freedom with this term). For example, a teacher could create a downloadable app (Fig. 2) where students could check their grades, assignment due dates, weekly agenda and so forth (Blue Hat), in an exercise that would empower the students whilst also giving the individuals involved the chance to manage their time and expectations, and realise their weaknesses and obstacles they face in the case they realise they are struggling with algebra for example (Black Hat). The possibilities are endless in this case study, since this same teacher could also create a reward system embedded in this app, where students are awarded “virtual coins” when tasks and homework are graded or finished. This case study demonstrates how connectivism and behaviourism could be successfully used with ICT to enhance students’ engagement, whilst encouraging to think about time management, big picture, focus, agenda, summary (Blue Hat), and risk, weaknesses, consequences, obstacles and potential issues (Black Hat).

Fig. 2. ClassDojo By Class Twist Inc. Source: iTunes Store.

Final considerations

These devices should not necessarily replace ‘traditional’ tools for the sake of ‘substitution’, perhaps for the purpose of superficially labelling ourselves as ‘progressive’ because we can pepper some ICT throughout our courses. The key question here is ‘how can ICT be used as a ‘tool’ in the classroom to enhance and transform teaching and learning?’. Depending on the purpose, mobile phones may do this. Sometimes.

It looks rather unrealistic to make the use of mobile devices generally acceptable given that some students will gravitate towards anything but their work. Finally, like the different answers given by different respondents, the best approach to avoid conflict with such a topic is to view the situation from a variety of angles, because the issue is not the mobile device, the issue is the individual and how the individual uses it inside or outside the class.

==================================================================

2. A REFLEXION ON BLOOM’S TAXONOMY AND SAMR MODEL

This is a simple reflection on Bloom’s Taxonomy and the SAMR Model. The first is a very important concept used worldwide and developed by a group of researchers in 1956. The concept was named after Benjamim Bloom, which was the leader of the mentioned group of researchers (Bloom et al., 1956). The latter was developed by Dr. Ruben Puentedura, which argues that this model “supports and enables teachers to design, develop, and infuse digital learning experiences that utilize technology” (Churches, 2011).

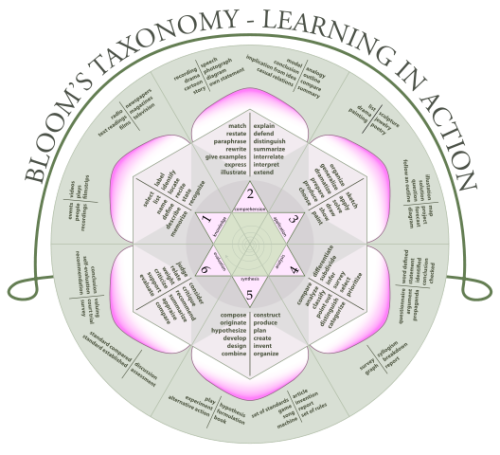

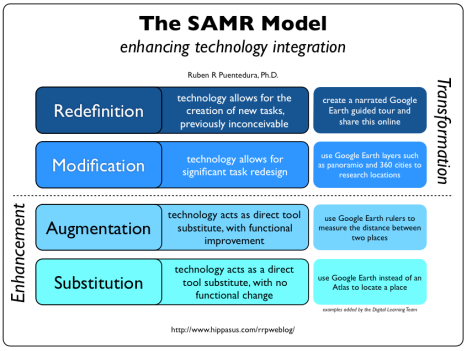

Bloom’s taxonomy (Fig. 1) is a valuable tool that can assist teachers to create intellectually challenging literacy tasks and units of work. This can be done by using the taxonomy as a scaffold, or guide, in the design process of lessons and units. The SAMR model (Fig. 2) emulates a Bloom’s classification somewhat, as there are deemed ‘lower’ or more simple ways of using ICT in pedagogy, and then there are ‘higher’ ways of using ICT to enhance pedagogy, the latter of which should enhance students’ opportunities to engage in higher order thinking.

Fig.1. Bloom’s wheel, according to the Bloom’s verbs and matching assessment types. The verbs are intended to be feasible and measurable. Source: K. Aainsqatsi

Fig. 2. The SAMR Model by Dr. Ruben Puentedura.

However, the levels between Blooms and SAMR have a major difference: the lower levels of SAMR (substitution and augmentation) are arguably unnecessary for educational purposes. For example, why ask students to conduct a ‘web quest’ when they could conduct a ‘book quest’ in the library? The outcome would possibly be the same, if not better, if students relied on the resources in the library to conduct their investigations. A webquest would simply augment the amount of information students had access to, which could also be a good thing (or not!), especially if they are equipped with the tools to decipher reliable sources of information on the web. Now, if the purpose of the lesson was for students to practise the skill of deciphering reliability (say in a History class), then one could argue that this webquest activity could be classified as a modification activity, only relevant and achievable because of ICT.

The point is, that sometimes students may be asked to use ICT for ICT’s sake. Teachers need to reflect on the purpose of using a particular ICT tool. It is not necessary to use the ‘lower’ level of the SAMR model to improve student outcomes because you would simply be asking students to do the same thing, or more of the same thing, using a different mode of delivery. It is desirable for teachers to use ICT in relation to the higher levels of SAMR. In this way, the use of ICT would be purposeful and enhance higher order thinking skills, which is what we should be aiming for. The lower levels of SAMR are not necessary to achieve this goal (in most circumstances, I would assume).

In comparison, the lower levels of Blooms could act as a vital part of scaffolding knowledge and understanding that leads to higher order thinking. Although Bloom’s is not necessarily used as a linear process, the lower levels would still foster foundations that could be built upon to enhance higher order thinking.

The classification of cognitive processes into ‘levels’ can help the teacher to reflect on the purpose of a unit of work. A simple question to ask oneself is ‘what should the students be able to do or create as part of the final assessment?’. If, for example, the final assessment does not require the students to analyse, synthesise, evaluate or create anything, then it could be argued that the unit of work has design flaws because it only requires students to use simple cognitive processes to answer basic questions.

Of course, the more basic cognitive processes outlined in the first 3-4 levels of Bloom’s are necessary to provide context, knowledge and understanding about topics and concepts. However, this should always be followed by a requirement for students to engage in higher-order thinking processes, such as analysis, synthesis and evaluation. Otherwise, students may not be challenged inside classrooms or progress from one zone of proximal development to another. Although, this is also dependent upon a teacher’s ability to pinpoint each student’s ‘zone’ (through data, formative assessments etc), which is a different topic to Bloom’s. The point is that Bloom’s can be used as a tool by teachers to help students progress once their ‘zones’ have been identified – using higher-order thinking strategies as the ‘bridge’. Likewise, SAMR’s higher levels can also act as a ‘bridge’, using ICT as the infrastructure.

References:

Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Churches, A. 2011. Published by Hawker Brownlow Education.

Images

Fig. 1. K. Aainsqatsi (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)%5D.

Fig. 2. Image the creation of Dr. Ruben Puentedura, Ph.D. http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/

Great blog – typo in Sub-heading 2 – SARM.

Very readable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, Jeanette.

Thank you for your visit and comment, and thank you for pointing out that typo 🙂

Regards

Paulo

LikeLike