Nowadays, teachers are expected to teach students who are ‘digital natives’. The conversation has shifted from ‘should we use ICT in schools?’ to ‘how might ICT be used most effectively?’. This mind shift has caused education departments across the globe to consider the implications for teaching practice. Some of these implications include understanding how students learn in the digital era and how these skills relate to constructivism and connectivism. It is also about understanding how teachers can use models such as Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (“TPACK”) and Substitution Augmentation Modification Redefinition (“SAMR”) to reflect upon their teaching practice when they embed ICT, and whether or not they are designing learning programs that engage critical thinking and activate students’ zones of proximal development. These are sizeable implications that require teachers to not only embed ICT into their programs, but to also assist students in understanding the opportunities and threats that the Internet, or ICT tools, present to them. In this way, a teacher’s role is to help students navigate, to some extent, this digital world and to be reflective and critical of what it has to offer.

It is important to embed ICT into the curriculum because technological skills are required for the advancement in education, work and for the overall participation in today’s interconnected world. In the western world, most students have continuous access to the Internet and the digital world; therefore it has contributed significantly to the rewiring of brains and affects how students learn. Nowadays, students regularly read, view, create and publish online multimodal texts and these can and should be used as tools to engage students in knowledge and understanding of different curriculum areas in schools. However, ‘traditional’ learning theories should not be forgotten in this context, and it is important to remember that part of the constructivist theory calls for learning to be scaffolded by ‘more knowledgeable others’. Indeed, this role would normally belong to the teacher and parents; however the more modern learning theory of ‘connectivism’ purports that students reinforce topics and concepts presented in class by accessing online material that contextualises information in a way the student can understand. Therefore, it would seem that the ‘more knowledgeable others’ has expanded to include not only a student’s teacher and parents, but also any online publisher. This indicates that schools and teachers need to find ways to teach students explicitly about how to evaluate online sources. This will guide how they participate as a citizen – as they will learn how to consume reliable texts and critique or discard dubious ones.

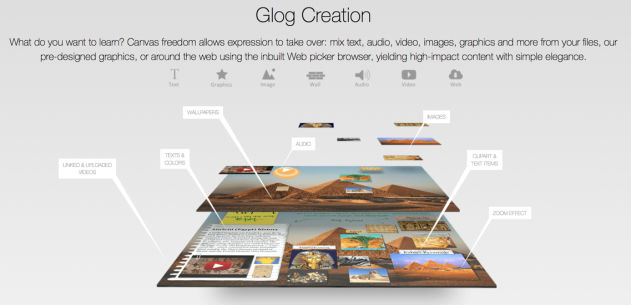

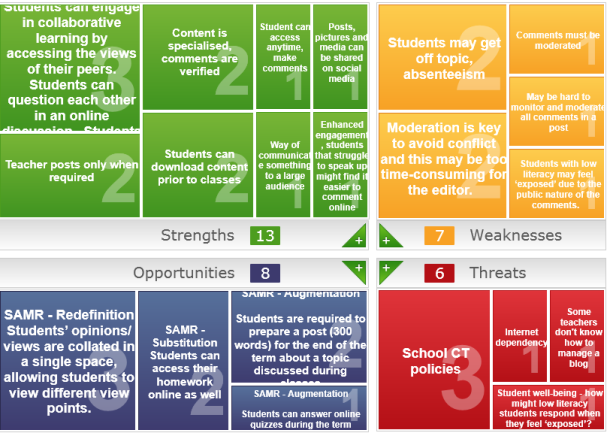

ICT can be used to connect students and to expose them to ‘more knowledgeable others’, which are aspects of the connectivist and constructivist theories respectively. Teachers can achieve this by using learning strategies such as collaborative learning when they embed ICT into their programs. For example, a blog or Facebook page where students can comment and contribute ideas in a ‘public’ space (that, is with their fellow classmates, or a wider audience if appropriate) would allow other students to consider the views of their peers. Students could practice critiquing each other in a respectful way in this public space, which might lead some students to see ideas from different perspectives and to potentially change their stance. In this scenario, the teacher would be the chief editor of the page and could police comments, pose questions and provide regular feedback to individuals and to the group, thus acting as ‘the more knowledgeable other’. This approach would also allow the teacher to construct a safe learning environment and mitigate any personal risk to everybody involved by ensuring that inappropriate content isn’t published or any personal details made public. It would also act as an opportunity to model safe and ethical online conduct, by respecting others in the online space. Such a blog or Facebook page used for collaboration is an example of using an ICT tool for a proper purpose: to enhance the learning experience.

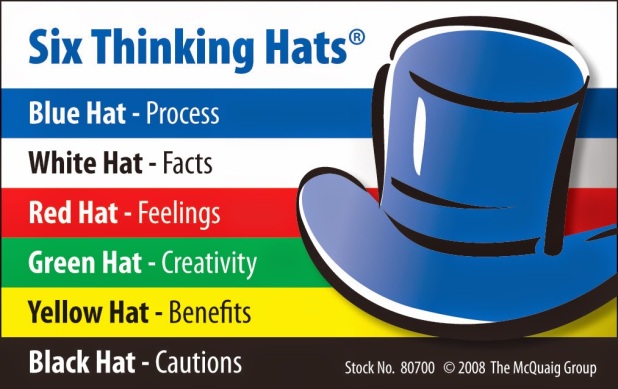

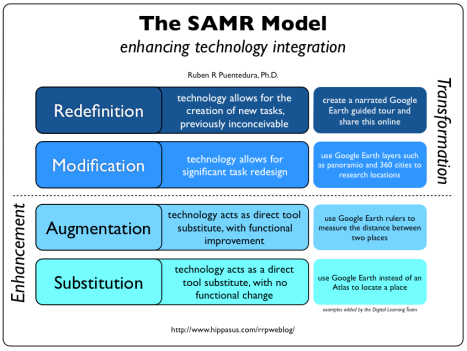

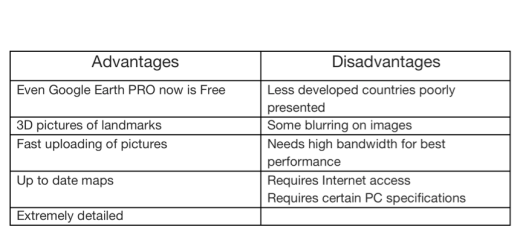

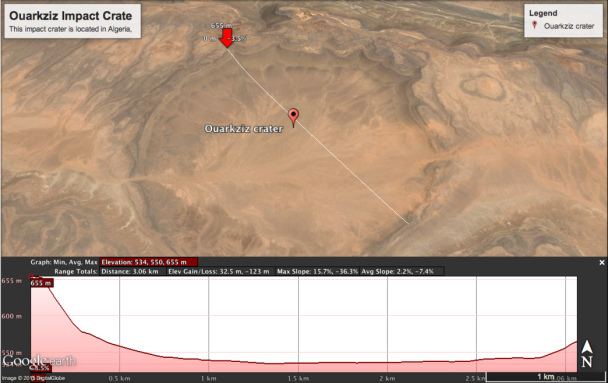

Teachers must always seek to use ICT in their learning programs for a proper purpose. Teachers can reflect upon and critique their digital pedagogies by using the TPACK tool and the SAMR model. These tools and models will demonstrate whether ICT is being used to support and enhance learning, or whether it is being used ‘for the sake of it’. For example, the SAMR model assists teachers to reflect upon whether an ICT tool is truly transformative in nature by redefining a particular task or project. For instance, Google Earth can redefine activities in a Geography class, as students would be able to take snapshots and zoom in and out of different landforms to analyse their features, which could potentially increase a student’s understanding of the concept through advanced imaging technology, allowing the student to visit and analyse places they cannot go. This was simply not possible prior to the introduction of Google Earth. On the other hand, a teacher may create a task such as a webquest; however the same information could just as easily be accessed through visiting the library and reading books. In this instance, the webquest would be a simple substitution for a library ‘book quest’, thus adding no value to student learning. TPACK and the SAMR model interconnect in this way, as both require a teacher to reflect upon the true purpose of using an ICT tool and whether or not ICT is being used to access and process subject matter in a way that will enhance a student’s understanding.

References

Atherton, J, S,. (2011) Learning and Teaching; Constructivism in learning [On-line: UK] retrieved 23 April 2015 from http://www.learningandteaching.info/learning/constructivism.htm

Beetham, H. & Sharpe, R. (2007) Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age. Routledge, NY.

Brenda Mergel’s article “Instructional Design & Learning Theory”(optional reading).

http://www.ttf.edu.au/what-is-tpack/what-is-tpack.html

Re-conceptualizing “Scaffolding” and the Zone of Proximal Development in the Context of Symmetrical Collaborative Learning.

The Age: How digital culture is rewiring ou brains. http://www.theage.com.au/it-pro/how-digital-culture-is-rewiring-our-brains-20120806-23q5p.html (newspaper article)

Fig. 4. Lesson plans at Google Earth’s website. Source: Google Earth.

Fig. 4. Lesson plans at Google Earth’s website. Source: Google Earth.